Fish eyes

We often think of the same information at different levels or abstraction. Here's a simple example:

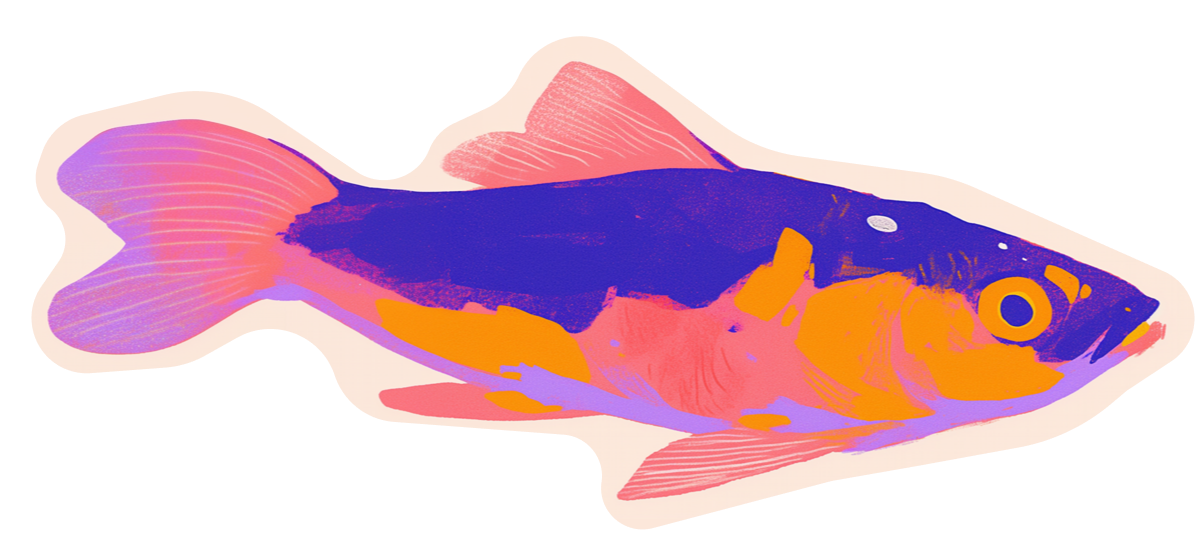

Here's a close-up of a fish— we can see the scales, the texture of the fins, the faint reflection in the eye.

Zoomed out a bit, the details are faded slightly. The surrounding ocean comes into view.

Zooming out more, the fish is just a few splashes of color amongst a school of fish.

Maps work in a similar way.

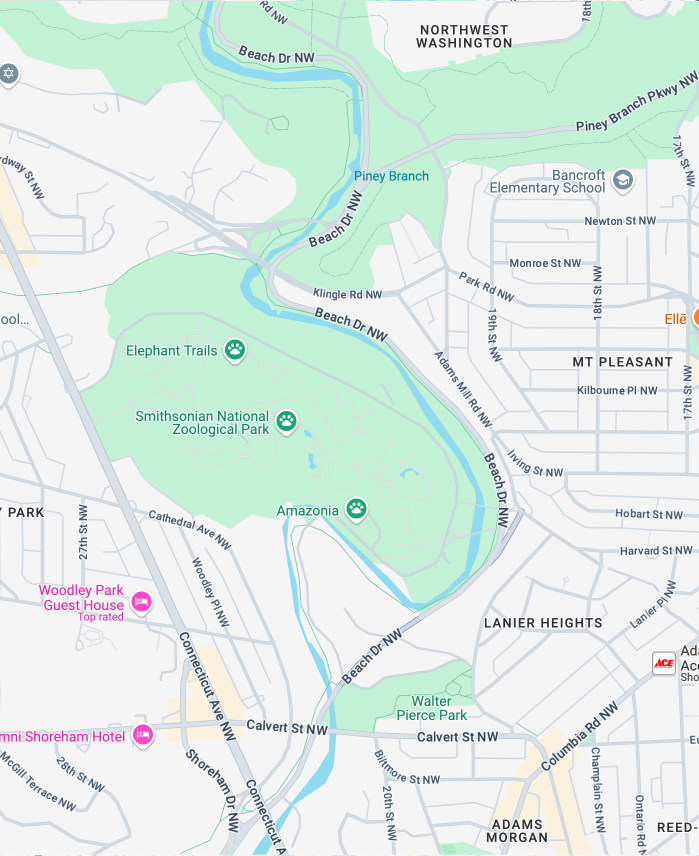

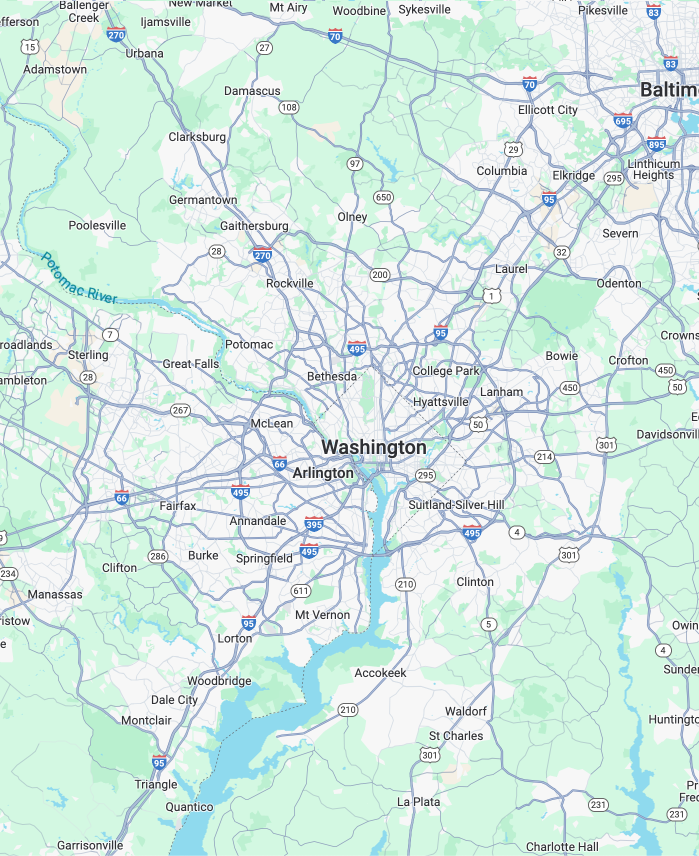

Looking at a section of the National Zoo, we can see paths, buildings, and even animal enclosures!

Zoomed out a little, and now it’s about neighborhoods—parks, stores, and streets.

Keep zooming out and you’re looking at a city, with just the highways and terrain.

Each level gives you completely different information, depending on what Google thinks the user might be interested in. Maps are a true masterclass for visualizing the same information in a variety of ways.

So far, these are familiar examples. What if we applied the same principles to text?

Let's take a look at the opening paragraph of The Metamorphosis.

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. He was laying on his hard, as it were armor-plated, back and when he lifted his head a little he could see his domelike brown belly divided into stiff arched segments on top of which the bed quilt could hardly keep in position and was about to slide off completely. His numerous legs, which were pitifully thin compared to the rest of his bulk, waved helplessly before his eyes.

Abstracted a little, we can remove some of the detail.

Gregor Samsa wakes from troubled sleep to find he's become a giant insect. He lies trapped on his hard shell-like back, observing his new segmented belly and thin legs moving helplessly.

And fully zoomed out, we can summarize the paragraph in a single sentence.

A man unexpectedly transforms into an insect while sleeping.

See how we can view even text at different levels of abstraction? For the interested, there's a little more detail in my AI Engineer Summit talk from 2023.

Showing multiple levels at once

Viewing the same text at different levels of abstraction is powerful, but what, instead of switching between them, we could see multiple levels at the same time? How might that work?

Let's look at an analogy from photography. A portrait lens brings a single subject into focus, isolating it from the background to draw all attention to its details. A wide-angle lens captures more of the scene, showing how the subject relates to its surroundings. And then there’s the fish eye lens—a tool that does both, pulling the center close while curving the edges to reveal the full context.

A fish eye lens doesn’t ask us to choose between focus and context—it lets us experience both simultaneously. It’s good inspiration for how to offer detailed answers while revealing the surrounding connections and structures.

Often, we’re handed a single piece of text, stripped from its surroundings: a quote from a book, a paragraph from a Wikipedia article, or a sentence from a movie script. You're left filling in the context on your own, and often incorrectly.

Take this quote from The Game of Thrones:

Winter is coming.

Without the backdrop of the looming threat in Westeros, this is just a weather report. Within the series, it’s an ominous warning of existential danger. Viewing quotes out of context is like trying to understand a movie by watching one scene: inherently incomplete.

Imagine you’re reading The Elves and the Shoemaker by The Brothers Grimm. You come across a single paragraph describing the shoemaker discovering the tiny, perfectly crafted shoes left by the elves. Without context, the paragraph is just an intriguing moment.

Now, what if instead of reading the whole book, you could hover over this paragraph and instantly access a layered view of the story? The immediate layer might summarize the events leading up to this moment: the shoemaker, struggling in poverty, left his last bit of leather out overnight. Another layer could give you a broader view of the story so far: the shoemaker’s business is mysteriously revitalized thanks to these tiny benefactors. Beyond that, an even higher-level summary might preview how the tale concludes, with the shoemaker and his wife crafting clothes for the elves to thank them.

The Elves and the Shoemaker

This approach allows you to orient yourself without having to piece everything together by reading linearly. You get the detail of the paragraph itself, but with the added richness of understanding how it fits into the larger story.

This specific example isn't the best, but alas there are only so many hours a day to play with code with a baby around. But I can imagine variations on it that would be more compelling. Even just a "grab a quote" interaction for articles that inserts some context around the quote would be really useful.

Think about how we typically learn. Pick up a book, and context surrounds every piece of information. Chapters give structure, connecting each idea to the ones that came before and after. A good author sets the stage, immersing you with anecdotes, historical background, or thematic threads that help you make sense of the details. Even the act of flipping through a book—a glance at the cover, the table of contents, a few highlighted sections—anchors you in a broader narrative.

Think about learning something from a person. Let’s say a friend tells you about fancy goldfish. Their explanation doesn’t stop at naming the Oranda—they might tell you where they first saw one, why they think it’s fascinating, or how it’s a beloved species in Chinese culture, symbolizing luck and prosperity. The context of who is telling you the information—their expertise, interests, or personal connection—colors how you understand it.

Or take museums: when you see a fish displayed in an exhibit, the plaque beneath it doesn’t just name the species. It tells you where the fish lives, how it evolved, and maybe even its significance in art or mythology. The exhibit places the fish in an ecosystem of knowledge, helping you understand it in a way that goes beyond just a name.

Zooming Beyond the Answer

But when you ask an LLM chatbot, you don’t get any of that. It’s as if you opened a book to one random sentence, read it, and closed the book again. Sure, the answer might be accurate, even helpful—but it’s stripped of all the surrounding context that makes learning feel meaningful and complete.

Let's say you take a photo of a fish on vacation and want to know what it is.

What fish is this?

This appears to be a type of fancy goldfish, likely an Oranda or Fantail Goldfish, recognized for its flowing fins and vibrant coloration.

Not a bad answer, really! But we're fully zoomed in on just the answer to our question. Sure, you can ask follow-up questions—what does the Oranda eat, where does it live, how does it compare to other goldfish?—but the onus is entirely on you to know what to ask next. The chatbot is reactive, not proactive, and unless you’re already an ichthyology enthusiast, you might not know the right questions to even start exploring deeper.

Let's reimagine Wikipedia a bit. In the center of the page, you see a detailed article about fancy goldfish—their habitat, types, and role in the food chain. Surrounding this are broader topics like ornamental fish, similar topics like Koi fish, more specific topics like the Oranda goldfish, and related people like the designer who popularized them.

Clicking on another topic shifts it to the center, expanding into full detail while its context adjusts around it. It’s dynamic, engaging, and most importantly, it keeps you connected to the web of knowledge.

Fancy Goldfish

Fancy goldfish are a domesticated variety of bred for unique physical characteristics and ornamental purposes. Unlike common goldfish, they have distinctive features such as bulging eyes, elaborate fins, and rounded body shapes. Originating in , these decorative fish are popular in home and ornamental . They come in various colors and types, including , , and goldfish. While beautiful, fancy goldfish generally have shorter lifespans and are less hardy than their wild counterparts due to selective breeding.

You’re learning around a concept, immersing yourself in a connected web of ideas where one answer sparks curiosity about the next.

What else could this apply to?

Where else could we apply a fish eye lens?

Timelines

Timelines

Key milestones are richly detailed and surrounding events fade into summaries, helping you see history as a dynamic continuum. Code

Code

Picture a code editor where the function you’re working on is fully expanded, related functions are summarized nearby, and the overall structure of your codebase is abstracted above. Education

Education

Textbooks or online courses could layer concepts so students can navigate effortlessly between detailed lessons and broader summaries. Task management

Task management

A to-do list could highlight today’s tasks in detail while showing summaries of weekly goals and overarching projects.

The beauty of a fish eye lens for text is how naturally it fits with the way we process the world. We’re wired to see the details of a single flower while still noticing the meadow it grows in, to focus on a conversation while staying aware of the room around us. Facts and ideas are never meaningful in isolation; they only gain depth and relevance when connected to the broader context.

This concept isn’t new—it’s foundational to fields like data visualization. A single number on its own might tell you something, but it’s the trends, comparisons, and relationships that truly reveal its story. Is 42 a high number? A low one? Without context, it’s impossible to say. Context is what turns raw data into understanding, and it’s what makes any fact—or paragraph, or answer—gain meaning.

The fish eye lens takes this same principle and applies it to how we explore knowledge. It’s not just about seeing the big picture or the fine print—it’s about navigating between them effortlessly. By mirroring the way we naturally process detail and context, it creates tools that help us think not only more clearly but also more humanly.